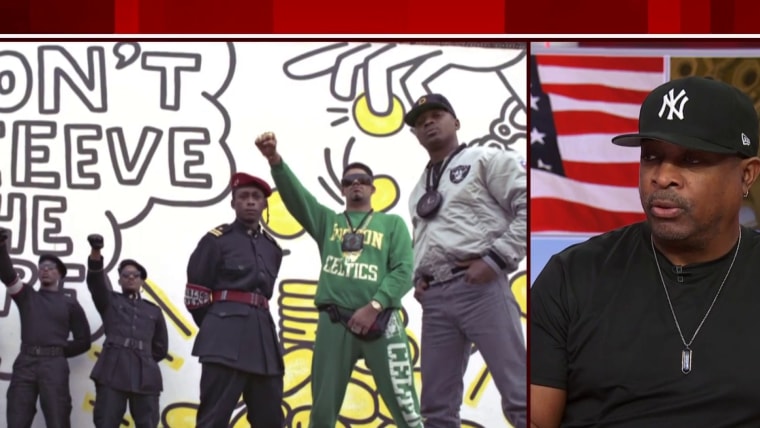

Hip-hop — more specifically, rap music — has always had an uneasy relationship with the law. As rap music was “the CNN of the ghetto,” as Public Enemy’s Chuck D put it, it also chronicled the Black experience with law enforcement and the courts from myriad angles and called out the inequities within those core institutions. Whether it’s KRS-One’s “Sound of da Police” or Akon’s “Locked Up,” there’s at least one hip-hop song for every step of the criminal justice system, from police interactions and arrest to trial, sentencing and incarceration.

Even as rap music has served as a platform to tell the truth about the criminal justice system, there’s been a consistent attempt by that system to criminalize the music.

Even as rap music has consistently served as a platform to tell the truth about Black America’s interactions with the criminal justice system, there’s been a consistent attempt by people in that system to criminalize the music, including its narratives about the system.

Long before Florida — along with other state governments and multiple local school boards — began its crusade to censor Black authors, officials, including federal officials, tried to silence Black musicians’ narratives about Black people’s lived experience. On the 1988 song “F--- tha Police,” the members of N.W.A likened themselves to prosecutors as they called out the racist brutality of the Los Angeles Police Department, brutality the whole world would see less than three years later when LAPD officers were caught on camera beating Rodney King.

But that song put N.W.A in the FBI’s crosshairs. In 1989, a spokesperson for the agency sent the group’s record company a letter that criticized the song for encouraging “violence against and disrespect for the law enforcement officer.” In that letter, the spokesperson, Milt Ahlerich, wrote: “I wanted you to be aware of the F.B.I.’s position relative to the song and its message. I believe my views reflect the opinion of the entire law enforcement community.’’

The common theme between today’s censorship of books and history lessons and past mobilizations against hip-hop is the attempted suppression of Black voices and truth-telling, particularly when those narratives seek to hold America responsible for not living up to its promise to all of its people.

Repeated attempts to criminalize rap music stand as, perhaps, the most glaring example of how First Amendment protections don’t apply equally to all. 2 Live Crew’s 1990 release “Banned in the U.S.A.” featured the Recording Industry Association of America’s first Parental Advisory sticker. The sticker was a result of a campaign against certain lyrics that was led by Tipper Gore, the wife of Sen. Al Gore, the future vice president. A federal judge had ruled 2 Live Crew’s previous album, “As Nasty as They Wanna Be,” was too obscene to be sold or performed in some parts of Florida. And the artists were performing songs from that album at a 1990 Florida show when they were arrested and booked for obscenity. While 2 Live Crew ultimately prevailed on appeal in a landmark victory for First Amendment rights, this wasn’t the last time we would see the law attempting to use rappers’ lyrics against them.

Repeated attempts to criminalize rap music stand as, perhaps, the most glaring example of how First Amendment protections don’t apply equally to all.

Though rap music was born in New York in the 1970s and increased in popularity in the early 1980s, the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s are widely considered to be rap’s golden age. That’s when it was growing out of its status as a subculture within urban America and becoming mainstream pop culture. And with that, its artists were giving some listeners a view of what life was like in the places that few would ever venture to.

This is not insignificant when we consider that the 1980s brought us the crack epidemic, which gave rise to significant gang activity, which led to an increase in violent crime across the country. These trends continued into the early 1990s. Then, after they’d witnessed their neighborhoods’ being turned upside down and besieged, many in Black America sought assistance from the federal government. We sought safety, protection and economic opportunity — essentially, the same things Black people have wanted since Reconstruction: an unencumbered path of access to the American dream. What we got, though, was a crime bill that offered mass incarceration as the panacea for our ills.

All of this was beautifully chronicled in the music. It may have seemed to some that so-called socially conscious artists such as Arrested Development or those groups that formed the Native Tongues were the polar opposites of so-called gangster rappers like Snoop Doggy Dog, Tupac or UGK, but they all helped tell a cohesive narrative about a system that wasn’t working. For example, A Tribe Called Quest’s “Eight Million Stories” and Ice Cube’s “It Was a Good Day” both depict an urban landscape, one in New York and the other in Los Angeles, and each narrator’s frustration with crime is paired with at least an equal amount of disdain for the police.

The tapestry that was rap music included language and cultures from all of America’s forgotten places and, together, stories of resilience, survival and, yes, fun. However, there was an irony: America was hearing rap music, but it was never really listening.

“Eight Million Stories” and “It Was a Good Day” both depict an urban landscape, one in New York and the other in Los Angeles, and each narrator’s frustration with crime is paired with at least an equal amount of disdain for the police.

Many people were interested in how rap’s style could be monetized or its lyrics could be weaponized but had little interest in its substance and failed to appreciate the nuance, creativity or imagination in so many of its lyrics. For example, in Main Source’s “Just a Friendly Game of Baseball,” Large Professor draws striking analogies between law enforcement and America’s favorite pastime. His references to sports and violence aren’t intended to focus excessively on either more than the entirety of the song’s being a clever exercise in wordplay.

The inability of many in the general public to see rap musicians as creative artists is a main reason the line between fiction and reality became blurred and rap music, its artists and those who enjoyed it were viewed through an anti-Black lens of criminality. Not only was being Black in America barely legal; now people’s expression of their lived experience was also subject to arrest and prosecution.

For decades now, prosecutors have used rappers’ lyrics and creative expressions as evidence in cases against them. This controversial practice is built on the assumption that such musicians aren’t real artists and that there is no separation between who artists are in real life and who they or their alter egos say they are when they’re in a recording booth or on a stage.

As a former assistant district attorney, I know that the assumptions jurors make about rappers and their lyrics often give prosecutors an enormous advantage at trial. We are seeing this play out in real time in Fulton County, Georgia, in the RICO trial of rapper Young Thug and his YSL record label. Prosecutors say his lyrics amount to a confession to the crimes they’ve charged him with. If you believe that’s reasonable, ask yourself whether you’d have supported a prosecution of Johnny Cash in which his song “Folsom Prison Blues,” with the lyric “I shot a man in Reno,” was treated by prosecutors as a confession.

The criminalization of rappers’ creative expression prompted Reps. Hank Johnson, D-Ga., and Jamaal Bowman, D-N.Y., to author legislation last year that seeks to limit the degree to which prosecutors can use rappers’ lyrics as evidence against them.

Ask yourself whether you’d have supported a prosecution of Johnny Cash in which his lyric “I shot a man in Reno” was treated by prosecutors as a confession.

Not only would that legislation install an important guardrail to protect rappers’ First Amendment rights, but it would also increase their chances of getting fair trials if they’re ever accused of crimes. Hip-hop turns 50 at the same time we’re witnessing an all-out assault on America’s democratic institutions and an all-out assault on rights of historically marginalized group to tell their stories or create art.

Just like the 2 Live Crew victory was a win for a country that says it values free speech, the passage of a bill that limits how lyrics could be used as evidence would also be a major win. Because these are protections that should be afforded to us all.

This is a critically important inflection point for how we navigate the connection of one of Black America’s most treasured forms of individual expression to the protections that are supposed to be afforded to all of us. But this is a much greater issue than rap, rappers or lyrics. If rap artists can be criminalized for what they say and aren’t allowed to speak freely, then those of us who aren’t rappers don’t have that freedom, either.

This post is part of MSNBC’s “Hip-Hop Is Universal” series, which celebrates the genre’s 50th anniversary and examines its future.