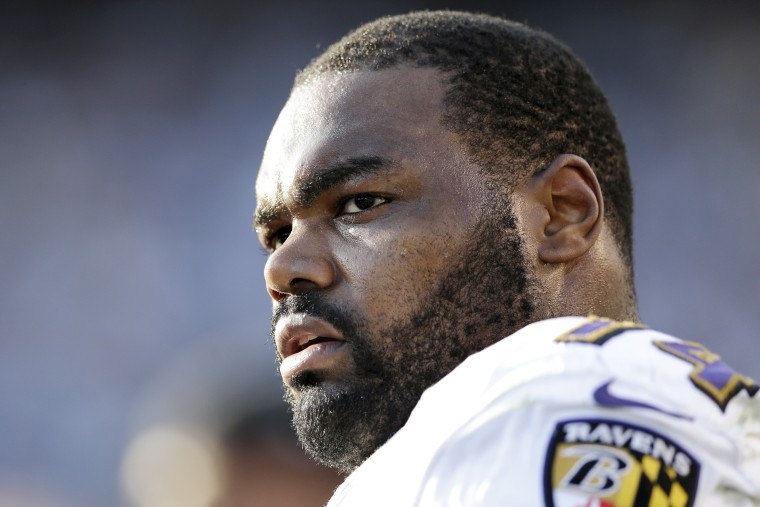

Earlier this week, former NFL player Michael Oher, the central character in the book and movie “The Blind Side,” filed a petition alleging fraud against the people who told him he was family. Oher alleges that when he was 18, Leigh Ann Tuohy and her husband, Sean Tuohy, tricked him into signing away his rights to control his financial future, and even the rights to his own name and life story, by convincing him that he was signing documents that would make him a legal member of their family. Oher said that what he actually signed was a contract agreeing that the Tuohys would be his conservators and not, as they led him to believe, his parents.

Oher said that what he actually signed was a contract agreeing that the Tuohys would be his conservators and not, as they led him to believe, his parents.

The Tuohys say they are shocked and saddened by Oher’s lawsuit and deny they behaved fraudulently toward him. Sean Tuohy says the conservatorship wasn’t a ploy to cheat Oher out of earnings, but an arrangement that was necessary to allow Oher, who grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, to attend and play for the University of Mississippi, Tuohy’s alma mater. Sean Tuohy told The Daily Memphian, "We contacted lawyers who had told us that we couldn’t adopt over the age of 18. The only thing we could do was to have a conservatorship." Despite what Sean Tuohy says he was told, Tennessee does allow 18-year-olds to be adopted.

It’s unclear at this point if the 37-year-old Oher’s case against the Tuohys has merit, but nothing’s unclear about the 2009 movie that catapulted Oher and the Tuohys into fame. It was typical, Hollywood white savior nonsense that, unsurprisingly, made hundreds of millions of dollars.

While Oher’s lawsuit is an indictment of sorts against the Tuohys, it is just as much an indictment of movie audiences that over and over again lap up stories about white people saving some downtrodden Black person or some downtrodden group of Black people.

Oher told us a long time ago that he didn't like the movie or the impact it had had on his life. "People look at me and they take things away from me because of a movie. They don’t really see the skills and the kind of player I am. That’s why I get downgraded so much, because of something off the field," Oher, then a left tackle for the Charlotte Panthers, told ESPN almost six years after the movie's release. “This stuff, calling me a bust, people saying if I can play or not ... that has nothing to do with football. It’s something else off the field. That’s why I don’t like that movie.’’

But his objections weren’t taken seriously. That’s probably because the white public craves feel-good stories that portray them as heroes more than accurate stories that portray Black people as complete and complex human beings.

“The Blind Side,” where a relatively small white woman, played by Sandra Bullock (who won an Oscar for her role), develops a relationship with a large Black teenager who had experienced homelessness is a twisted version of “Beauty and the Beast.” It excites a white imagination that longs for contact with the Black other and simultaneously fears that contact. Similar to what Joseph Conrad did in his 19th-century novel “The Heart of Darkness,” the Black person is considered dangerous or irreparably damaged until a white person sees their humanity.

The white public craves feel-good stories that portray them as heroes more than accurate stories that portray Black people as complete and complex human beings.

Of course, the white savior flick can also double as the “magical Negro” flick where the Black character — such as the one Michael Clarke Duncan played in “The Green Mile” or the one Whoopi Goldberg played in “Ghost” — is there to help white characters become the best versions of themselves. As Nnedi Okorafor writes in her short story “Magical Negro,” the Black character isn’t a real person, just a rhetorical device that's there to help save the hero from themselves.

Oher isn’t a fictional character, but a real-life person. Even so, the movie reduces him to a gentle giant with unrecognized promise. And who recognizes his promise? Not the Black people he grew up around with, but a well-off white couple: the Tuohys.

Even more than the fantasy of white people saving Black people, movies such as “The Blind Side” are fantasies of racial harmony. Think of Michelle Pfeiffer’s character in "Dangerous Minds." That character, a teacher, goes into the modern-day “heart of darkness,” the so-called inner city. She’s challenged and tested but eventually wins over the hearts and minds of Black people. And everyone gains from the encounter. The white person is the hero, without whom the Black characters, we’re left to believe, would never have been anything.

The Tuohys are portrayed in a similar manner. And movie audiences would rather believe such a dream than engage in the difficult work of fighting for the kind of structural social change that would benefit everyone, even those a heroic white person never encounters.

The white person is the hero, without whom the Black characters, we’re left to believe, would never have been anything.

Heartstrings aside, there is a great deal of money to be made by feeding into the mainstream’s racial fantasies. Playwright Radha Blank rallied against these twisted incentives and the way they box us all in her fantastic movie “40 Year-Old Version,” but she also demonstrates what it’s like to turn our backs on those rewards and risk finding our own voices.

As a sociologist in a field that helped invent this racist and paternalistic treatment of Black people as fundamentally damaged, I teach against those familiar narratives. Those narratives are dishonest, condescending and emotionally manipulative, but, put them on the big screen, and you’re almost guaranteed to make a whole lot of money.