This Supreme Court term we were expecting a monsoon. Instead, we got a run-of-the-mill downpour. Did the high court pull the country to the right on issues that will deeply affect millions of people? Absolutely. Look no further than the court’s decisions to effectively ban affirmative action in higher education, to protect a religious objector who successfully argued that it harmed her speech rights to have to comply with a state’s anti-discrimination law and make wedding websites for gay couples, and to limit the ability of the federal government to protect the environment. But the court didn’t go nearly as big and as far as it could have. In key areas, a majority of the court opted to maintain the status quo instead of upend our settled laws.

The court pumped the brakes. And that matters.

Conservative courts like this one are going to issue conservative rulings. Last term was a blowout: The majority erased the right to obtain an abortion from the Constitution, granted gun owners more rights and whittled away at environmental protections. The court set an almost insurmountably high bar to cross in terms of how conservative its rulings could get. So it’s notable that in this term, it didn’t get near that threshold with its rulings.

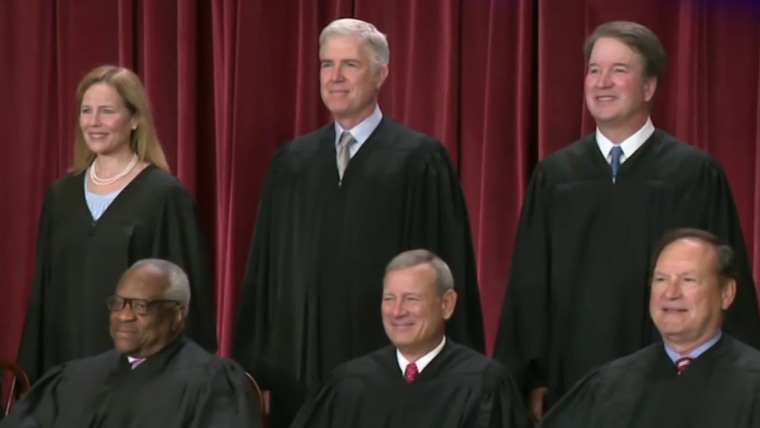

The majority of the court, often led by Chief Justice John Roberts, pulled itself back from setting off the legal version of an atomic bomb. In key cases the court maintained the status quo instead of speeding the country to the right. To be sure, the majority’s decision to maintain the status quo is different from a decision to issue liberal rulings. Those are a thing of the distant past, or future. Moderation may now be viewed as a victory among more liberal-leaning jurists.

But the court pumped the brakes. And that matters.

The most obvious example comes from a case out of North Carolina, in which Republicans asked the court to adopt a theory called the independent state legislature doctrine. This theory would undermine elections as we know them and allow state legislators to make decisions about federal elections free of oversight from governors, election administration officials and, most important, state judges. It would allow state legislators to do things like draw congressional district lines, move polling places and alter voting registration rules without any oversight from federal judges. While the court laid some land mines for future elections, Roberts, writing for the majority, largely discredited the broadest reading of this baseless theory. Some, including me, believed that because the court decided to review the case, it was prepared to adopt this theory, at least in large part. Luckily, we were wrong.

The court did something similar in a case dealing with voting rights in another case authored by the chief. The court reviewed a case out of Alabama, where Republican legislators drew congressional district lines in a way that diluted Black voting power in violation of the Voting Rights Act. The high court had put on hold a lower court decision that had ordered Alabama legislators to draw new district lines that complied with the Voting Rights Act. This served as a signal to many of us that the court was prepared to overturn the lower court ruling, which had correctly found a violation of the Voting Rights Act. Again, we were wrong. And again, Roberts, writing for the majority, opted, instead of further whittling away at voting rights, to maintain the status quo and agree with the lower court that state legislators violated the Voting Rights Act.

The court didn’t go nearly as big and as far as it could have. In key areas, a majority of the court opted to maintain the status quo instead of upend our settled laws.

Next up, two big cases asked the court to change the law concerning when social media companies can be liable for content their users post. The court was, in part, deciding whether to upend our decadeslong understanding that social media companies generally can’t be sued for words, videos and images that users post on their sites. Here again, while the court decided to hear the two cases, it ultimately opted to keep our current legal framework in place. The justices unanimously seemed to acknowledge that they shouldn’t be the ones setting internet policy.

And finally, in a subtler sense, the court also pulled back in the area of immigration law and allowed one of President Joe Biden’s policies to remain in effect. In that case, Texas and Louisiana challenged Biden’s immigration enforcement guidelines. Essentially, the secretary of homeland security created guidelines about who would be prioritized for arrest and deportation. Instead of getting to the merits of that question, the court concluded that Texas and Louisiana lacked legal standing to sue. This means that the policy, at least for now, remains in place.

To be sure, our yardstick for measuring how conservative a Supreme Court term is is skewed by how far the court pulled us to the right last term — and by the fact that we are largely judging only the cases the court decided to hear in the first place.

But there’s no ignoring a trend that emerged: holding the status quo in big cases that could have upended our understanding of elections, voting rights, liability for social media companies and immigration policies. This may be our new version of a legal victory.