Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy took aim at Merrick Garland on Sunday, warning that he will launch an impeachment inquiry against the attorney general if an IRS whistleblower’s allegations pan out. The exact backstory behind the threat is a complicated one, involving Hunter Biden and the GOP’s seemingly misguided belief that the president’s son got some kind of sweetheart deal.

McCarthy’s willingness to threaten Garland’s removal is an escalation of the House GOP’s monomaniacal focus on owning the Biden administration. It showcases a striking contrast with his predecessor, Rep. Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif. Pelosi often treated impeachment as an atomic bomb with a hair trigger — a powerful weapon whose fallout made it not worth using. McCarthy, on the other hand, prefers to swing impeachment around like a whiffle bat — seemingly threatening when bluffing, but useless as an actual tool for enforcement.

Pelosi’s reluctance to engage with impeachment at all in dealing with then-President Donald Trump was legendary. Democrats had only barely reclaimed the majority in the 2018 midterms and now that she had the speaker’s gavel back, she wasn’t about to let anything distract from her caucus’ agenda. That meant clamping down on any talk of impeachment, even in the face of Trump’s ongoing profiting while in office and pressure from the left to hold him accountable.

There have been even fewer cases of the House passing articles of impeachment against Cabinet members than presidents at this point.

When the Mueller Report offered a potential roadmap to investigate whether Trump obstructed justice, Pelosi preferred to move on. It was only when it became clear that Trump had tried to extort Ukraine’s government that she yielded and opened an impeachment inquiry. Even then, she kept a tight grip on the reins as the House eventually passed two articles of impeachment along party lines.

In contrast, Republicans have been much less circumspect overall about the idea of trying to remove President Joe Biden from office. Their pretenses have varied but seem universally flimsy when you consider that the GOP all but vowed retribution against the next Democratic president after Trump’s impeachment. As we saw on Sunday, McCarthy himself hasn’t been shy about using the “i-word” — but rather than going after Biden directly, he’s preferred to set his sights lower.

The Constitution provides that not just the president, but the “Vice President and all civil officers of the United States” are subject to impeachment. The phrase “civil officers” is pretty vague, but historically has been taken to mean members of the executive branch and the federal judiciary. But there have been even fewer cases of the House passing articles of impeachment against Cabinet members than presidents at this point. The first and only example was Secretary of War William Belknap in 1876, who resigned before the House’s investigation was complete and he was acquitted in the Senate.

Despite that history, McCarthy was threatening Homeland Security Secretary Alexander Mayorkas with impeachment just days after last year’s midterm elections. The speaker blamed Mayorkas for “the greatest wave of illegal immigration in recorded history,” even though crossings began to increase during the Trump administration. Mayorkas has been a favorite target for Republicans, given his role in implementing the Biden administration’s immigration policies.

The bar that Article II, Section 4 sets for impeaching a president — “treason, bribery, and high crimes and misdemeanors” — is just as high for other civil officers. That’s generally been understood to mean something beyond simply being bad at your job or disagreeing over policy, but earlier this month a House subcommittee held a hearing on Mayorkas’ supposed “dereliction of duty” that could fuel a future impeachment effort.

Pelosi saw impeachment as a divisive and time-consuming effort, and she was right — to a degree

With only a five-vote majority in the House, though, securing even a hyperpartisan impeachment vote will require evidence of wrongdoing that simply hasn’t emerged against Mayorkas or Garland, let alone Biden. To his credit, McCarthy does seem to know the limits of his ability to actually put that rhetoric into action. Both last year and on Sunday, he was careful to threaten an impeachment inquiry, not impeachment itself.

It’s an important distinction — while there aren’t really rules governing the impeachment process beyond precedent, an impeachment inquiry is a beefed-up version of a typical congressional committee investigation. At least that’s the argument that Pelosi and House Democrats used when trying to force the Trump administration to hand over documents it was withholding in 2019. But launching an inquiry doesn’t guarantee that articles of impeachment will be drafted, let alone passed.

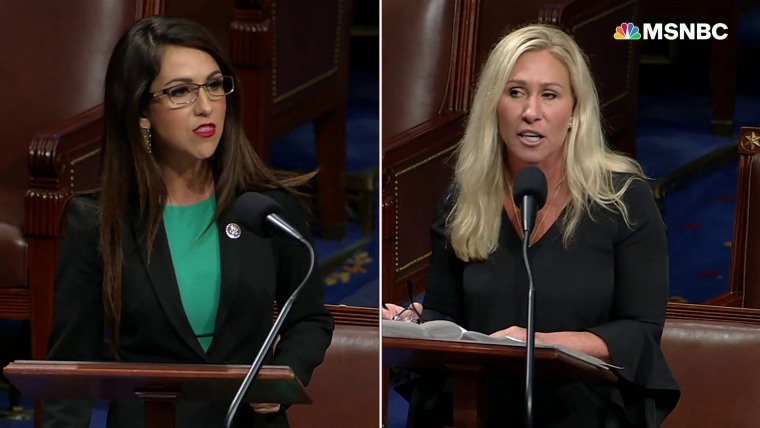

Whether his members have caught onto that distinction is a bit shakier. Just last week, Rep. Lauren Boebert, R-Colo., nearly forced a vote on articles of impeachment against Biden himself. It was only at the last minute that leadership avoided having members vote on passing or tabling the draft articles by instead sending them to committee.

Even in the case of Mayorkas and Garland, though, McCarthy has reason to be wary. Any potential trial would have to go through the Democrat-controlled Senate, where a two-thirds Senate majority would be needed to convict. And Senate Republicans have shown little interest in removing Mayorkas via impeachment; somehow I doubt they’ll feel much more intensely about Garland.

Pelosi saw impeachment as a divisive and time-consuming effort, and she was right — to a degree. Her hesitancy, forged in the aftermath of the Clinton impeachment, made sense politically, but failed to hold the president accountable as Congress is responsible to do. McCarthy on the other hand has rightly judged that while impeachment does nothing to bridge the partisan divide, it does serve as a unifier for his fractured caucus. In throwing the threat of it around to score easy political points, however, he is cheapening it in the same way the GOP accused Democrats of doing when confronted with Trump’s actual offenses.