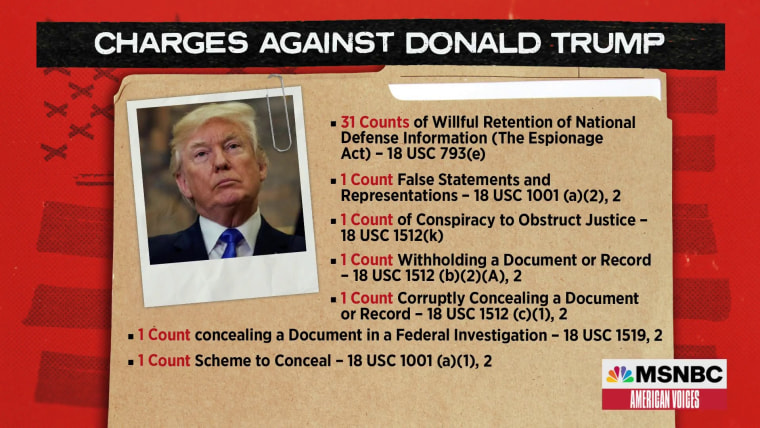

The federal criminal case against former President Donald Trump is damning. If the federal prosecutors can prove even a portion of what is detailed in the 49-page indictment, then a jury should convict Trump on charges related to obstructing justice and unlawfully retaining national security information. Then the federal judge presiding over the trial should sentence him to prison. During his arraignment in a federal courtroom in Miami Tuesday, Trump's attorney responded to the 37 felony counts against him by saying, “We most certainly enter a plea of not guilty.”

We’re not talking about any criminal defendant and any federal judge. We’re talking about a former president and a federal judge appointed by the criminal defendant

But we’re not talking about any criminal defendant, and we’re not talking about any federal judge. We’re talking about a former president and a federal judge appointed by the criminal defendant who granted one of his baseless legal motions in an earlier iteration of this case.

Federal judges have broad discretion over legal proceedings. They dictate the pace of cases, decide which evidence will be heard by the jury and which evidence won’t be, how jury selection will proceed, and even if a case will ever go to the jury. If you’re a federal criminal defendant, who your judge is is no small matter.

Hence, U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon’s decisions can make a huge difference to the trajectory of the federal criminal case against Trump. Cannon, using the power that all federal judges possess, could employ a portion of the federal rules of criminal procedure to hand the former president a legal win that is entirely unreviewable. That’s right. As unlikely as it may be, it is possible that Cannon could substitute her own judgment for that of a jury and acquit Trump on all of the 37 counts he faces. While this would be a nuclear option for Cannon, one that no judge concerned about her reputation or legacy would choose, there are also other, smaller ways that she could assist Trump in this case.

To be clear, the fact that Trump appointed Judge Cannon isn’t the reason we should fear she will make rulings that unfairly favor him. It doesn’t follow that being nominated by Trump means doing Trump’s bidding. Many of Trump’s other judicial nominees, for example, rejected his (legally baseless) attempts to overturn the 2020 presidential election. Therefore, Trump's appointment of Cannon isn’t by itself a reason to worry.

We should worry about the judge’s impartiality because of a ruling she made in an earlier stage of this very case where she acted more like a legal advocate for the former president than a neutral arbiter overseeing a historically significant case.

Cannon, without any legal grounding to do so, granted Trump’s request for a special master to review the documents the FBI obtained in August during the execution of a search warrant at Mar-a-Lago. Cannon’s outrageous ruling was reversed by a panel of judges, including two appointed by Trump, in the conservative 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. In addition to saying the district court “stepped in with its own reasoning” and reached an “unsupported conclusion,” the panel wrote, “The law is clear. We cannot write a rule that allows any subject of a search warrant to block government investigations after the execution of the warrant. Nor can we write a rule that allows only former presidents to do so.”

Concerned about bias Cannon might show the president who nominated her, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., asked during Cannon's 2020 Senate confirmation hearing if she'd had “any discussions with anyone — including, but not limited to, individuals at the White House, at the Justice Department, or any outside groups — about loyalty to President Trump?”

"No," Cannon said.

If Cannon continues to act more like a member of Trump’s legal team than a judge, she could create a legal headache for the Department of Justice. She could even create a disaster. For instance, every federal judge has broad discretion over scheduling matters in her courtroom, and if she decides to move slowly, Cannon could all but guarantee that any trial would happen after the next presidential inauguration. If Trump, or any other Republican, wins the presidency, that president could direct his attorney general to seek to dismiss this case. And if Trump is inaugurated again, then he could attempt to pardon himself.

Federal judges can make pre-trial rulings that eliminate the Justice Department’s ability to present crucial pieces of evidence.

Federal judges can make pre-trial rulings that eliminate the Justice Department’s ability to present crucial pieces of evidence. If Cannon finds, for example, that certain pieces of information prosecutors deem crucial cannot be properly introduced as evidence in trial, then that alone could be a big boost for Trump’s defense. We already know that Trump’s legal team plans to challenge a judge’s determination that the crime-fraud exception to the attorney-client privilege applies. That decision allowed the DOJ to obtain evidence from Trump’s former attorney that was used in the indictment.

How could this play out? Imagine a situation in which the jury never learns that, as the indictment details, Trump apparently suggested his attorneys lie on his behalf and told them, “Wouldn’t it be better if we just told them,” meaning federal investigators, “we don’t have anything here?”

A federal judge oversees the process of jury selection. Cannon, therefore, has large discretion to determine who is and isn’t seated on the jury. She gets to decide, for instance, which jurors will be dismissed for cause, that is, dismissed based on her belief the juror can’t be fair. It goes without saying that finding jurors who can set aside their personal and political beliefs and fairly and neutrally apply the facts of this case to the law is vital.

But, again, it’s at least within the realm of possibility that the jury is never allowed to weigh in on this case. According to Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 29, after a jury is sworn in and the prosecution has finished presenting its evidence, a federal judge can unilaterally determine that there isn’t enough evidence for a conviction. Such decisions are not reviewable by an appellate court on the grounds that it would violate the Constitution’s prohibition against trying a defendant for the same crime more than once.

If an average citizen named Donald Smith were named in this indictment with this kind of evidence, then it would be hard to imagine him escaping a conviction.

Is this likely? No, Rule 29 motions, while routinely requested by defendants, are rarely granted. But there is a reason Trump has been nicknamed Teflon Don, a moniker symbolizing his apparent ability to escape the consequences of his actions. If an average citizen named Donald Smith were named in this indictment with this kind of evidence, then it would be hard to imagine him escaping a conviction. But because we’re not only talking about Trump, but also talking about a federal judge who has already been chided for stepping in with her own reasoning, it’s not quite as hard imagining Trump pulling it off.

She probably won't, but in the interest of justice, the rule of law, and the integrity of the judicial branch, Cannon should recuse herself. Not because Trump appointed her, but because she carried his water in an earlier iteration of this case and because she has immense power over this one.